Our Lady of Darkness

Fritz Leiber's novel, True Detective, George Sterling, Jack London, and Bohemian Grove. Full of spoilers for everything.

At the recent Annual General Meeting of the Friends of Arthur Machen, I acquired a 1978 Fontana paperback edition of Fritz Leiber’s Our Lady of Darkness. I had been meaning to read it for a while. Although not a Leiber devotee—I somehow never got to Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser when a Dungeons & Dragons-playing teenager—I had very much enjoyed his ‘Black Gondoliers’ recently and was intrigued by what I had heard about Our Lady. I have also been teaching Thomas de Quincey’s Suspiria de Profundis for the past two years—from which the title of the novel is lifted—and become fascinated by the mysterious, melancholy allure of the constituent essays or prose poems, which seem to absorb the reader into a narcotised molasses of oneiric yet palpable grief (or something).

I knew that the superb Swan River Press in Dublin had brought out a new edition of the original iteration of Our Lady of Darkness, under the title The Pale Brown Thing, and I had been getting round to buying what I knew would be an impeccably well-produced hardback. However, at the traditional book sale at the FoAM AGM, I acquired the Fontana version for about £1. So that’s what I read. It’s an odd novel and was overall an uncomfortable reading experience, but not in the way I’m convinced Leiber intended. It is ultimately something of a shaggy-dog story and increasingly metatextual as it progresses—I lost confidence in some of my criticisms by its conclusion, because I wondered if they were part of the ludic conceit of the whole.

I’ll get my objections out of the way first: the dialogue consists of very over-written exposition and info-dumps, with every character speaking in dense fact-laden paragraphs, sometimes concluding in a jarring fragment that suddenly reminds you that they’re meant to be a person interacting with another person. Here’s an example from pages 129–30 of my edition:

‘Besides being one of America’s few great novelists, Hammett was a rather lonely and taciturn man himself, with an almost fabulous integrity. He elected to serve a sentence in a Federal prison rather than betray a trust. He enlisted in World War Two when he didn’t have to and served it out in the cold Aleutians and finally toughed out a long illness. No, he’d have been interested in a queer old duck like de Castries and showed a hard, unsentimental compassion towards his loneliness and bitterness and failures. Go on, Donaldus.’

This is obviously not how people speak or interact with each other IRL, but it is the only way people speak and interact with each other in Our Lady of Darkness. The protagonist, Franz Westen, is a clear avatar of Leiber himself and they share many autobiographical details, such as recent widower-hood, recovery from alcoholism, profession (author of weird fiction) etc. This makes some aspects of Westen’s characterisation a bit Mary Sue, or whatever the middle-aged, male, sleazy, self-serving version of a Mary Sue might be termed. This mainly manifests itself in a consistent prurience around young—sometime disturbingly young—women: the downstairs neighbour Cal, a twenty-something classical musician, of course just so happens to be ‘into older men’ i.e. Westen, despite at times looking like ‘a serious schoolgirl of seventeen’. Oh dear. Things get even worse with Westen’s preoccupation with his landlady’s 13-year old daughter, and then truly vile with an almost-casual anecdote concerning the then-child of a bookseller. I am generally very resistant to what someone smart I know calls ‘tedious moral audits of the past’ but there’s stuff in here which really doesn’t—thankfully—get a pass these days, if it ever did. Westen’s attraction to young girls is at least entirely passive (it appears), but the troubling thing to the reader is that I don’t think Leiber presents this attraction as anything other than a plot device. I don’t think we are meant to be appalled. It’s rather couched in the sort of licentious 70s sleaziness that seems mericfully now very dated; the sordid, grubby backwash of the 60s sexual revolution, references to ‘swingers parties’ included. I hope it’s clear that I found this aspect of the novel repellent.

That aside, I can fully understand why it has developed its reputation: it is a love-letter to weird fiction, and is replete with allusions to other stories and authors, some of whom become characters themselves: Clark Ashton Smith, Lovecraft (of course), but also more obscure references to an intricate array of other minor literary figures. This is what we these days call really good fan service, and I appreciated the pleasing frisson of recognition. Leiber not only conflates reality with the fiction he’s writing, but also has his fictional characters provide commentary on this conflation: for example, Donaldus (himself a fictionalised version of the real-life poet Donald Sidney-Fryer, detailed in this excellent blog post) remarks upon the unlikely similarity of the name of the mysterious (fictional) occultist Thibaut de Castries to that of the real-life author and Lovecraft collaborator Adolphe De Castro. This is all clever stuff, creating a really unsettling, disorientating palimpsest of reality and literature, which at the climax Leiber, with great legerdemain, reveals to be the in-novel source of the horror itself. Even this conceit is itself a play on M. R. James’s ‘Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad’; Our Lady of Darkness is cumulatively a hall of mirrors—disorienting reflections through many glasses darkly—and I admire it very much for its success in this undertaking. I admire it perhaps more than I enjoyed reading it.

As well as a ludic metatextual commentary, the novel is also an occult thriller, reminding me at times of Aleister Crowley’s The Moon Child (Crowley of course puts in an appearance in Our Lady)—particularly in terms of the impossibility of disentangling the roman-à-clef from the fiction—and also the Illuminatus! trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, which—as well as sharing the same countercultural, free-wheeling 70s Californian milieu—also uses an accumulation of historical incident and authentic biographical detail to add a verisimilitude to its central conspiracy theory (which is, I suppose, exactly how conspiracy theories function). And talking of conspiracy theories brings me to one of the main points of interests of the novel for me, personally: George Sterling.

George Sterling was an ultimately suicidal Decadent poet of the early twentieth century, and a well-known locus of Bohemian life in San Francisco and California. He achieved particular recognition during his lifetime for his 1907 poem ‘A Wine of Wizadry’—like Arthur Machen’s The Hill of Dreams a prime example of late-flowering Decadence that was soon to be eclipsed by the emergent Modernism the movement was midwife to. I first became interested in Sterling because of his mentorship to the young Clark Ashton Smith, who was to become one of the Weird Tales triumvirate alongside Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. Smith, under Sterling’s guidance, became at 19 the ‘Keats of the Pacific’ with his collection The Star-Treader and Other Poems (1912). In London, the volume received a very enthusiastic review by Machen in the Evening News. Clark Ashton Smith’s diary is a central plot device in Our Lady of Darkness, and Sterling appears in several of the constituent historical anecdotes (flash backs?), together with Jack London.

However, the first time I encountered a fictionalised version of George Sterling was in another San Francisco-set novel, Jack London’s Martin Eden (1909, which I first became aware of because it’s what the young hoodlum Noodles reads on the toilet in Serge Leone’s 1984 Jewish gangster epic Once Upon a Time in America). Martin Eden is a favourite novel of mine, albeit a very gloomy and even depressing one. One day I would like to write an in-depth comparison of the novel with Gissing’s New Grub Street: they’re a good transatlantic match, both concerning the vagaries of literary achievement, and the literary market, and the unsatisfactory relationship between artistic endeavour and success. But that’s for another time.

Sterling (as ‘Russ Brissenden’) appears in Martin Eden as an example of a literary purist pursuing an aesthetic, bohemian, alcohol-fuelled existence utterly adrift from the practicalities of life (despite his professed socialism); contrasting with Martin Eden’s own sense of manly responsibility, duty, and especially his authentic class-consciousness. After I had read Martin Eden and became intrigued by Jack London’s actual relationship with George Sterling, I was delighted to learn of the Californian bohemian milieu that hooked in not only Clark Ashton Smith but also Sterling’s own mentor, Ambrose Bierce. Bierce was on my mind because around the time I was reading Martin Eden, the first season of True Detective was—bizarrely—bringing consciousness of his Hastur/Carcosa pseudo-mythology to a vast HBO audience. Although it was Robert W. Chambers that developed Bierce’s fragmentary conceit with the lore surrounding the ‘King in Yellow’ and the ‘Yellow Sign’, it was Bierce who initiated the conceit, which was then absorbed haphazardly into the Cthulhu Mythos by Lovecraft and others after him, including Fritz Leiber. The first season of True Detective hinged around an occult conspiracy theory: a cabal of sinister patriarchs were abducting, abusing, and murdering young women and girls, possibly under the auspices of some sinister supernatural agency related obscurely to the ‘Yellow King’ and mysterious ‘Carcosa’.

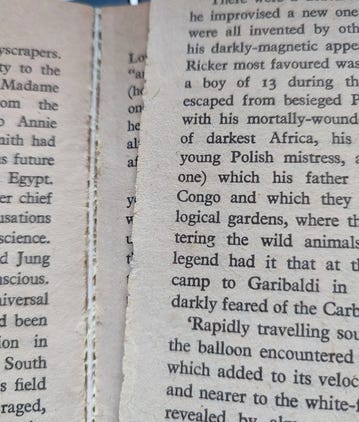

Reading about Sterling and Jack London at the time, coincidentally, I was astonished to discover that they were part of the original group that had established what became known as Bohemian Grove (pic of Sterling at Bohemian Grove below).

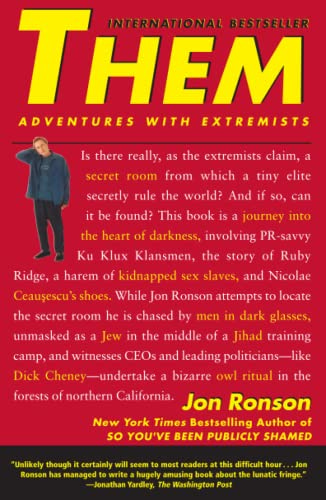

I was astonished because I had first heard of Bohemian Grove due to it being the subject of one of the central episodes of Jon Ronson’s hair-raising 2001 book of reportage Them: Adventures with Extremists. Ronson became aware of Bohemian Grove as an obsession of various conspiracy theorists: allegedly an annual Satanic ceremony in which major politicians up to and including the president, the very wealthy, and the great and the good—all men, natch—gather in a closely-guarded compound in remote Californian woodland and sacrifice infants to a giant statue or idol, under the auspices of some sinister supernatural agency, before discussing how to secretly rule the world for the ensuing year. This at any rate is the belief of Ronson’s conspiracy-theorising companion on his adventure trying to sneak in to the event. All Ronson himself sees is a bunch of wealthy old men giving themselves the opportunity to get drunk and behave in a silly fashion away from the glare of public scrutiny. Ronson’s companion is depicted as an eccentric, 20-something obsessive who is by turns charming and horribly belligerent. His name is Alex Jones. Fast forward several years and we all now know who Alex Jones is, and we all know that the QAnon conspiracy theory that contributed to the almost-derailment of American public life hinges on the belief of a cabal of sinister oligarchs sacrificing children. True Detective got there before them, through this strange back-route involving Bohemian Grove’s founders. Interestingly, the second season of True Detective, while wildly different in tone, again hinged around a cabal of sinister oligarchs exploiting children (to mix things up, for the third season the audience is encouraged to believe that a cabal of sinister oligarchs is murdering children right up to the final revelation that this actually isn’t the case at all).

I have no idea what to make of this strange dovetailing of weird fiction and ‘reality’, beyond it bringing me neatly (or messily) back to Our Lady of Darkness. The ‘pale brown thing’ in the end consists of a fardel of decaying pulp paper, the disintegrating pages of all Westen’s accumulated reading material. For me it also ended up being what I was holding in my hands by the end of reading the novel—its sepia leaves falling apart before my eyes. I was also thinking of all these other troubling associations, sketched out above, and wondering whether I was delineating and/or confecting my own conspiracy theory, or rather that Leiber’s conspiracy theory was seeping out from the cursed pages of the novel, and encroaching upon reality. If this was all part of Leiber’s design, then I am in awe.*

I might update this post at some point if I can make any sense of it. One thing writing this has prompted me to do is read Jack London’s 1913 novel Valley of the Moon, which features another appearance from George Sterling and the bohemian artists’ colony of Carmel, California, which eventually spawned Bohemian Grove.

*I don’t really think this: I think conspiracy theories emerge because it’s possible to make associations between things, because everything is of course inextricably connected—ideas, imaginings, events, people—which is no big revelation.