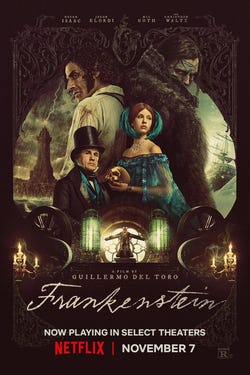

Frankenstein (2025)

A monster movie without a monster

Hot on the heels of Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu, another new cinematic iteration of a Universal Monsters OG. Or rather, a further entry in the more recent trend of stripping away the accumulated pop-cultural detritus of a century and getting back to the literary source material, Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, heavily revised by her for the 1831 edition. The novel has always had its detractors, with criticism largely aimed at an alleged naivety or stylistic ineptitude on the part of its author—remarkably, still a teenager when she wrote it. I, on the other hand, think it’s astonishing. So, does this new film do it justice? The answer is of course “yes and no”.

To its credit it is clearly a labour of love by del Toro and is perfectly cast—though I will get to some specific complaints about Oscar Isaac’s performance in due course. Jacob Elordi is terrific as the creature; effortlessly communicating various combinations of vulnerability, desperation, violence, strength, despair within the course of seconds; a being at war with himself as well as the world. The rest of the ensemble—Mia Goth, Christoph Waltz, Felix Kammerer—don’t have a huge amount to do, but do it well, while frequently struggling to compete against the lush, rococo, suffocating extravagance of the set and costume design. Del Toro knows his stuff and his decision to (presumably) use Bernie Wrightson’s peerlessly evocative interpretation of the creature as the basis for his one pays enormous dividends in distinguishing it from the Karloff archetype.

So, with all of these boxes ticked, why did it not really land for me? As mentioned, I have minor quibbles with Isaac’s interpretation of the good (bad) doctor: his generic British accent wanders distractingly over slightly different registers, with the vowels particularly betraying him at moments. Both he and del Toro are laudably going for moral nuance in the character—they respect the audience enough to leave it to them whether they sympathise or condemn. He is in no way “relatable”, which is a relief, and frequently downright vile. However, as written, there is an insistence on reducing the story to what amounts to a domestic psychodrama; Charles Dance, playing very much to type as an overbearing, cruel patriarch, physically abuses the young Victor “for his own good” and inevitably Victor visits the same torments on his own creation. There is a weirdly Freudian motif of milk drinking that is crowbarred in and then abandoned (father/blood and mother/milk, err, something something, very deep). Ditto the visions of a terrifying angel/demon/skeleton entity that haunt Victor, until they don’t.

Here is the crux of why it fails, though: Frankenstein’s creation never becomes a monster. Of course, he is treated as such, but this is consistently all through human cruelty or misunderstanding. His superhuman violence is depicted, sometimes in graphic, shocking detail, but this is when he is defending himself or ripping apart savage wolves, again defensively. The novel achieves real depth and sophistication because, in response to being ‘othered’ by the doctor and humanity more generally, the creature becomes monstrous. He persecutes. He wreaks vengeance. He murders in cold blood. He denounces Frankenstein, for making him do such things. Hence Frankenstein’s monster. Del Toro’s creature is entirely sympathetic—at each step we see how he has only ever meant to do good and has only ever been maltreated in response; sinned against and never sinning. We are always on his side and as a result, this is a monster movie without a monster. It is a defanged monster movie. It even has a moving (genuinely), happy ending in which the doctor and his creation reconcile before the latter wanders off into the sunset.

Terence Fisher’s Hammer version (The Curse of Frankenstein, 1957) went too far the other way, with the creature being a brain-damaged psycho we just want to see put down. It’s a difficult novel to adapt and I don’t think there’s ever been a film that has managed it, regardless of how good or otherwise each film has been in its own right. Thinking about this after watching del Toro’s film last night, I alighted on what is actually the best Frankenstein film, and it’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (Werner Herzog, 1974). I’m not simply being irritating—the story is the same one, essentially, and it engages properly—profoundly—with the philosophical themes which fascinated Shelley; Locke’s blank slate and Rousseau’s noble savage etc. No actual monster, admittedly, but as I say, neither has del Toro’s film.

One final note: I watched the film with my 11-year-old son, and he thought it was brilliant. He was completely engrossed and by turns outraged and upset by the maltreatment of the creature, and offered his own insights at particular moments—for example, when the creature appears in Victor’s chambers before the wedding, he was excited to inform me that “bro is cooked”. It is always a good corrective to watch a film with someone who isn’t a tedious cynic and sees the wonder in cinema, life etc.